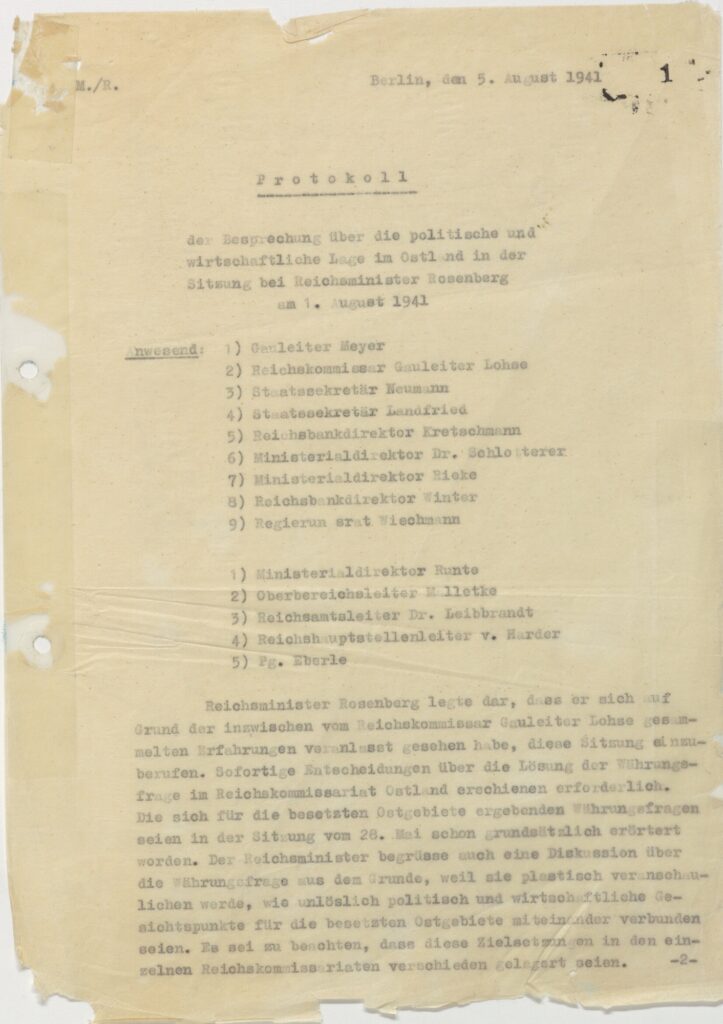

1941-08-01 Nazi High-Level Meeting on Occupied Eastern Europe: 10,000 Jews liquidated in Lithuania

On August 1, 1941, Reich Minister Alfred Rosenberg led a high-level meeting to discuss the governance of Nazi-occupied territories in Eastern Europe. Hinrich Lohse, the Reichskommissar for Ostland and Gauleiter of Schleswig-Holstein, reported that “approximately 10,000 Jews had been liquidated by the Lithuanian population”. Lohse emphasized that, following Hitler’s directive, “the Jews should be completely removed from this area”.